Doing Less with More

Renewable Energy Just Isn't Very Dense

Many of those who have been waiting with an increasing sense of urgency and frustration for the world to transition from using fossil fuels to completely renewable, carbon free energy sources are becoming vocal in their disappointment. A few are coming around to the realization that governments cannot solve the problem of carbon pollution simply by providing green tax incentives. That may sound like a classic case for more research and development, but the limitations of renewable energy have always been self-evident from a mass and energy balance perspective. Yes, we do still need to aggressively improve and expand renewable energy technologies. But, at the same time, we also need to understand why renewables will never be a seamless replacement for fossil fuels in certain respects.

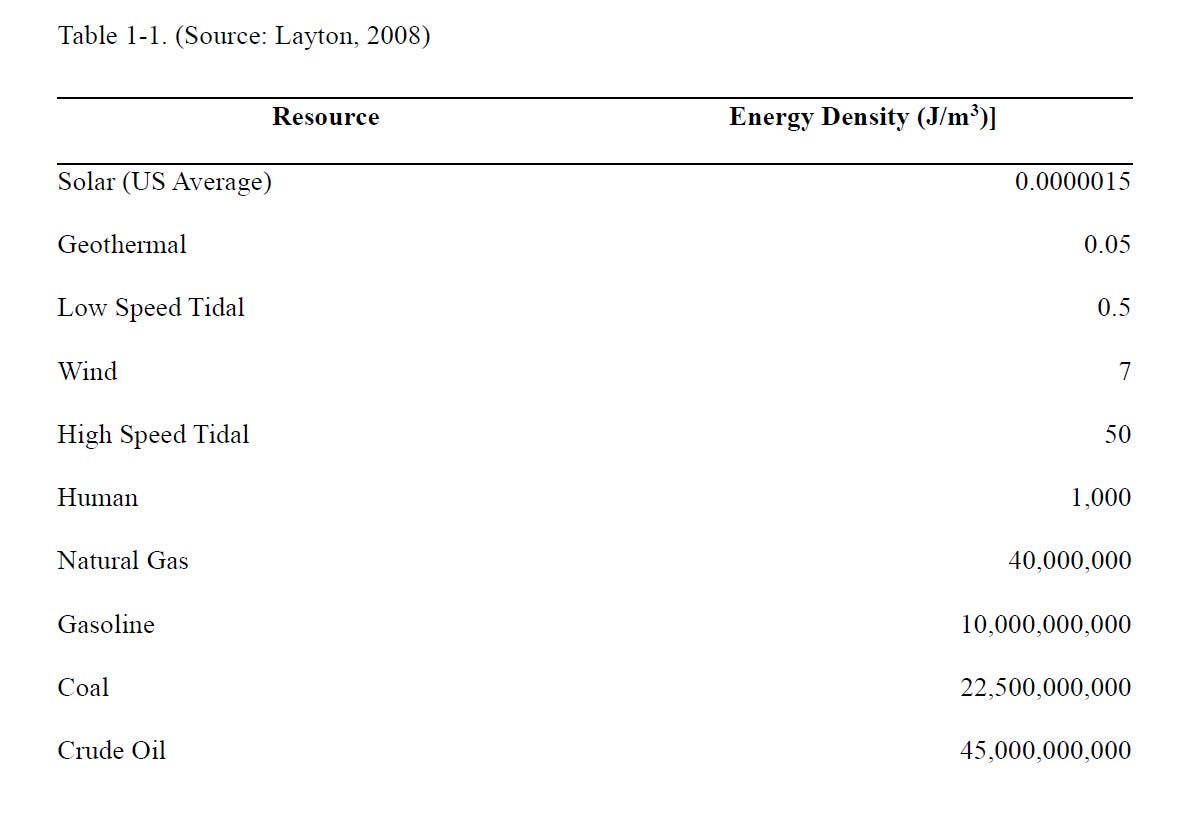

One reason that fossil fuels have been such a powerful and convenient source of energy for humanity over the past 300 years is that they are incredibly dense: they contain a huge amount of energy in a very small volume. In my upcoming book I discuss the link between energy density and the aspirations of the clean energy transition. The following table, which will appear in the book, illustrates the 16 order of magnitude difference between the energy density of solar radiation and that of crude oil. That’s 16 zeros. In other words, the volumetric energy content of crude oil is 30 million billion times as dense as the energy we can harvest directly from the sun.

Crude oil is liquid sunshine, stored painstakingly by Mother Nature over millions and millions of years. We all know the story in its most basic form. Tiny plants and animals died and were washed onto the beaches of ancient oceans, where they mixed into the sand and decomposed. As these beaches were gradually buried by new sand and rock layers, and shifted by tectonic forces, heat and pressure cooked the decayed organic material into hydrocarbons. The incredible amount of energy needed to do all of these things: grow plants, feed microscopic organisms, transport sediment, move tectonic plates—all of it came from the sun. It was compacted into tiny droplets of fluid inside tiny spaces in rocks thousands of feet underground. It was densified.

You can tell a very similar story for metals, or any other substance on Earth. Minerals have been concentrated by prodigious applications of time and energy into very convenient deposits which humans have (quite recently) learned to extract en masse. Some of us have belatedly recognized that consuming stocks of resources over a period of decades or centuries that would require hundreds of millions of years to regenerate naturally poses an existential problem for our species. We now wish to cut out time and geology as middlemen and directly harness radiant solar energy and the wind created by its uneven heating of the Earth’s surface. These “new” sources of energy are replenished every single day. Sadly, they are anything but dense.

The tradeoff between diffuse, renewable energy sources and the dense, finite fuels we have come to rely on is not just measured in terms of carbon pollution. Capturing the same amount of energy that can be pumped from an oil or gas well which, once drilled, is barely visible, requires many massive wind turbines or vast arrays of solar cells. Few people seem to want one of these things in their backyard much more than they want to live next to a nuclear power plant or a toxic waste dump. Land use constraints are a major impediment to developing renewable energy sources. The availability of specialized materials to build increasing numbers of wind and sun capturing devices is another. Innovation and experience can certainly help us to become more efficient sun farmers, but the 16 zeros problem of reduced energy density is never going to disappear. More renewable energy means more land, more metal, and more money will have to be diverted from other uses.

And this brings us to the growing competition for those resources. In the same way that much of the 20th century was spent fighting over oil—a tax we continue to pay in terms of defense budgets—the next century is likely to bear witness to wars fought over metals, water, and prime wind or solar generating real estate. It is no secret that some of the world’s leaders see a future in claiming ownership of minerals on the moon, or even in asteroids or more distant celestial bodies. For now, such goals lie squarely in the realm of science fiction. In the nearer term, expect more intense conflicts over terrestrial minerals, with the great powers jockeying for influence and control in places where “clean energy metals” such as lithium are plentiful (like South America).

A sustainable energy transition is possible, but it has to involve more than merely a pledge to reduce atmospheric carbon emissions. Unless we are committed to hopping from planet to planet in a mad quest for more natural resources (assuming this is ever feasible), quitting oil and gas will also mean going on an energy diet in absolute terms. As any dieter can tell you, that means making choices about what consumption choices are most important and making peace with having other desirable things placed out of reach. Trying to “win” the clean energy transition with military superiority, on land, at sea, or in space, is a long-term losing proposition that will only serve to shift the focus of attention from one suite of minerals (petroleum, coal) to others (cobalt, lithium, copper). It may work for a while, but only for a while.